|

The History |

The background to 1066 In the eleventh century, England was undergoing a period of turmoil. Aethelred II, called Unraed, which means poor council (although often translated as Unready), had been the king since 978. Although the Danes and English had been living in a period of relative peace for several decades, the Danes, who had settled along England eastern lands in an area known as the Danelaw, began raiding into English territory shortly after Aethelred became king. In response, Aethelred began paying Danegeld, essentially a bribe to stop the raids.

In 1002, Aethelred took action against the Danes when he ordered a massacre in Oxford on St. Brice's Day. Although the actual number of men killed is unknown, it spurred King Sveyn Forkbeard of Denmark to increase the pace and ferocity of his raids and in 1013, Sveyn became king of England and Aethelred fled to Normandy. Sveyn died a year later. English royal succession at the time was semi-elective in nature, with the new monarch selected by a council called the witanangemot. In the Anglo-Saxon held parts of England, Aethelred was recalled from Normandy, but in the Danelaw, Sveyn's son, Cnut, was elected. Cnut led an invasion of England in 1015. When Aethelred died in 1016, his son, Edmund Ironside took his place, but following Edmund's death later in 1016, Cnut became king of all England.

Aethelred's first wife, and Edmund's mother, Aelfgyfu, had died in 1002 and Aethelred had remarried Emma of Normandy, so when he fled to Normandy, he was taken in by Emma's family, her brother was Duke Richard II of Normandy. In 1003, Aethelred and Emma had a son, Edward, who spent most of his life being raised at his uncle's, and later his cousins' courts.

In England, Cnut was succeeded by his sons, Harald II and Harthecnut. In 1041, Harthecnut invited Edward back to England at the urging of the Bishop of Winchester and Earl Godwin of Mercia, the most powerful nobleman in England. Part of Harthecnut's intention seems to have been to identify Edward as his successor and when Harthecnut died in 1042, the nobles elected Edward to be the king over the kingdom where the Danelaw and the English lands had become somewhat united after twenty-six years of Danish rule. It is important to note that Harthecnut indicated he wanted Edward to succeed him, but the English also elected Edward to the position.

Godwin worked to forge an alliance with the new king by marrying his daughter, Ealdgyth, to Edward. The two were married, but had no children. In 1051, Edward quarreled with Godwin, resulting in Godwin and his sons fleeing England for about a year before they were able to return and reclaim their lands and power. That year abroad was fateful, however. During that time, Edward's first cousin, once removed, William of Normandy, visiting the English court. At the time, William was about 24 years old and had served as the Duke of Normandy since he was seventeen, despite his parents not being married (and hence his sobriquet, "the Bastard.") During this visit, Edward promised to make William his heir. While on the continent, it was within a lord's right to promise the succession to a hand-picked successor, in England such a decision would have to be ratified by the witanangemot, and not just at the time the promise was made, but when it came time for a new king, a concept which would have been foreign to William. Furthermore, in 1064, Harold found himself shipwrecked when a storm blew him to Ponthieu, between Normandy and Flanders. The Count of Ponthieu, took Harold captive and turned him over to William of Normandy, of only gave Harold his freedom after coercing acknowledgement that William would be Edward's successor. Not only did Harold have no power to promise the succession, but an oath made under duress is not binding.

When Edward died on January 5, 1066, the witanangemot elected Harold as the most powerful lord in England, as his successor. In Normandy, William planned, with papal approval, to invade England and take the throne for himself. In Norway, Harald Hardraada also decided he had a right to the English throne based on an agreement between Harthecnut and Magnus, his predecessor, in 1041. Of course, that promise had the same issues Edward promise to William had, it was never confirmed by the witanangemot, and wasn't likely to be.

There were no standing armies at the time, lords could call up the forces controlled by the nobles who had sworn fealty to them and in England, there were strict rules governing how long the troops could remain active and how many days they owed their lord each year. Expecting an invasion from Normandy, Harold called up his forces in the south and waited. On the other side of the channel, William also waited for the wind to change. The prevailing winds made an assault on England from Normandy untenable. An attack from Norway, however, was possible and Harald Hardraada attacked in the north, allying with Harold's brother Tostig. Harold rode north and on September 25, his forces defeated the invaders at Stamford Bridge, killing both Harald and Tostig. Harold immediately had to ride for the south, where the winds had shifted and William was now able to attack. Along the way, Harold had to rebuild his army.

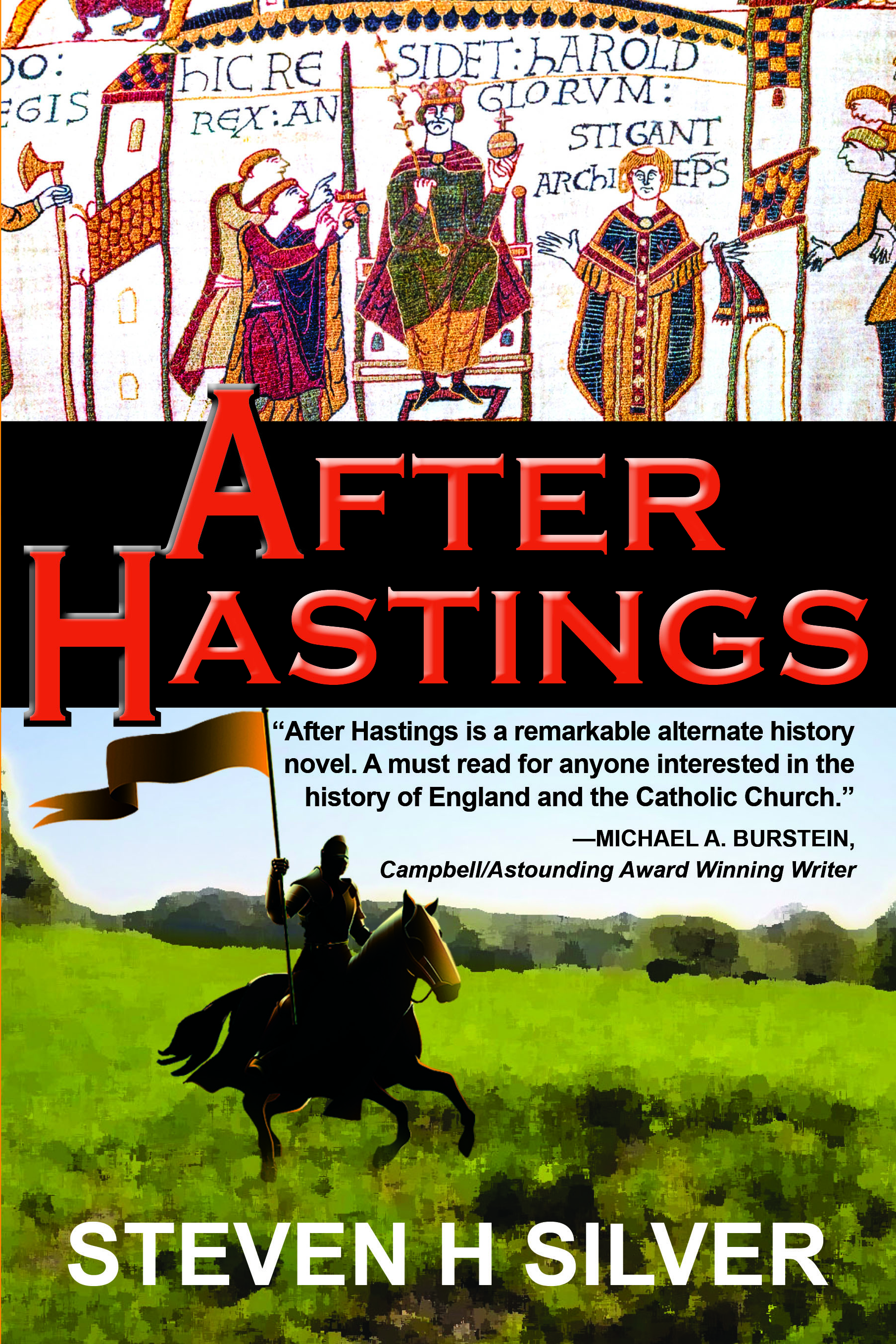

The Battle of Hastings Harold and William met in battle near the village of Hastings (also called the Battle of Senlac, for the hill Harold lined his troops up on). Harold's troops were exhausted, but they maintained a better defensive position. While the Normans employed cavalry, the English, even if they arrived on horseback, fought on foot. The Normans launched their attack shooting arrows up the hill at the English, which proved ineffective. Without English return arrow-fire, the Normans began to run low on arrows and William ordered his spearmen up the hill, where they were met with hurled spears, axes, and rocks. William's forces could not break through the English shield wall. A rumor appears to have circulated the William had been killed and the Normans began to retreat. This is the point where After Hastings departs from our own timeline. In the novel, William is unable to regain control of his men, but in reality, he successfully rallied his men and led a counter attack. The Norman feigned retreat throughout the afternoon. Through the course of the battle, Harold brothers Leofwine and Gyrth were both killed. William is also said to have had multiple horses killed from under him. Late in the day, Harold was killed when his eye was pierced by an arrow. Without a leader to fight for, the English defense collapsed and they fled the field of battle.

Following the battle, Gytha, Harold's mother, requested his body, but William denied it to her. According to legend, Harold's mistress, Ealdgytha Svannehals, wandered the battle field until she found his mutilated corpse and spirited it away to Waltham Abbey. Other stories tell that William ordered it thrown into the sea. There are also tales that Harold survived the battle and lived as a hermit in England's west country. Rudyard Kipling wrote a short story based on this legend.

The aftermath Throughout the rest of October and into November and December, William continued to make his way through the English countryside, accepting the submission of English nobles and clergy, including Archbishop Stigand of Canterbury. The leaders of the English submitted to William in Hertfordshire and on December 25, 1066, he was crowned king of England by Archbishop Ealdred of York at Westminster Abbey, which had recently been built by King Edward. Resistance to William's reign continued for several years and he often brutally put them down. In 1069, William faced a coordinated uprising in Northumbria and the subsequent Harrowing in the North devastated the region for centuries. While Northumbria had once been a focal point of English power, William's destruction reduced it to a backwater.

William reigned from 1066 until his death on September 9, 1087. He was succeeded in Normandy by his son, Robert Curthose, and in England by his son, William Rufus. Although England had made him a king, he tended to view it is subservient to his holdings in his native duchy of Normandy. An attempt by the Normans to reunite England and Normandy under Robert's rule in 1088 failed and in 1091, William Rufus successfully invaded Normandy, wresting the duchy from his brother. After William Rufus's death in the New Forest in 1100, his younger brother, Henry I took power in both lands, eventually leading to the Angevin dynasty, which ruled England and parts of France until 1485.